“A few days ago, a study was released that positioned Chile—and its pension system—as the eighth-best in the world: something very different from what is seen daily in our country.”

The pension system in Chile has been lauded as “a model for pension reformers around the world,” and the ‘Chilean model,’ in whole or in part, has been implemented around the region. In 2001, George W. Bush declared that the United States “could take some lessons from Chile, particularly when it comes to how to run our pension plans,” and later cited the Chilean model during his later attempt at privatization of Social Security.

Within Chile, however, the system is deeply and persistently unpopular. Calls for reform have been at the forefront of political debate since at least the 2006 elections. Prior to the events of this past week, the largest protests seen in democratic Chile were those calling for an overhaul of the current pension system. Currently, many news sources have mentioned pension reform as a key demand of protestors in Chile, and a keystone of the Government’s initial response to the protests was a battery of changes to the pension system.

So what’s going on? I’ll explain briefly the salient details of Chilean pensions and how they impact the present unrest here in Chile.

Pensions in Chile are mandated individual retirement accounts administered by private companies

Quick summary for Americans:

Chile has no equivalent to Social Security.

Instead, everyone is obligated by law to contribute to ‘401(k)-like’ individual retirement accounts, administered by private companies known as AFPs, to which your employer contributes nothing and where you have very little control over the distribution of your money.

The current system was established under the dictatorship as part of a larger effort to restructure the economy on the part of a small group of US-trained academics.

A safety net was put in place in 2008, following discontent with the lack of coverage for the poorest members of society.

Chile’s modern system of pensions was the child of José Piñera Echenique, the elder brother of current President Sebastián Piñera and “the pension world’s equivalent of Placido Domingo.” In 1980, J. Piñera—then Minister of Labor and Social Forecast under the military junta of Augusto Pinochet—initiated the process of phasing out the teetering patchwork of pension systems that then existed, to be replaced by a new, fully-privatized system. Previous public pension schemes were unfunded, or “pay-as-you-go,” similar to the United States’ Social Security in that benefits paid out at any particular instant were funded by current contributors. Instead, the new scheme would be fully-funded, where current contributors would not pay into the pension trust used to pay out benefits. Individuals pay into private pension funds; their lifetime contributions to these funds determines how much they would receive in benefits after retirement.

The businesses responsible for administering these funds are known as “Pension Fund Administrators" (<<Administradoras de Fondos de Pensiones>>), or AFPs. Participation in the AFP system is compulsory for all workers in public and private sectors. Exceptions include the military and police, which maintain separate pension systems funded through taxes, and those in the informal economy. As of 2019, seven operate in Chile. AFPs maintain investments in stocks, bonds, and government debt; after early reforms passed in 2002, AFPs must provide at least several different funds for subscribers to choose from.

The amount of the contribution to an AFP is left to the contributor, but must exceed 10% of pre-tax monthly income, up to 60 Units of Account (UF; approximately USD$2300 at the time of writing). For workers not self-employed, this portion is withheld from one’s paycheck by their employer, who then pays a sum corresponding to their employees’ contribution to their respective AFP. To recoup operating costs, AFPs charge various fees based primarily on contributions (not on the net amount in the fund). The portion of one’s income paid as a pension contribution is not taxed, although pension income is taxable and uses the same progressive scale as is used for regular income, in addition to the standard 5-7% taken as a mandated health care contribution. Pensions may be received as annual programmed withdrawals (distributed monthly), an immediate life annuity, a combination of the two, or as a temporary income with a deferred life annuity.

The system bears superficial similarities to the American 401(k) system in the sense that retirement funds are managed by investment managers, contributions are tax deductible, and withdrawals are taxed. However, employers do not pay into the retirement fund, which in keeping with the spirit of “individual capitalization” is designed to be completely self-funded. Furthermore, the money is disbursed from one’s AFP account according to a contract agreed upon at retirement; it is extremely difficult to withdraw funds from an AFP outside of this plan and absolutely impossible to withdraw anything prior to retirement.

In 2008, reforms introduced the “Basic Solidarity Pension” (<<Pensión Básica Solidaria>>) for those without pensions, generally those in the informal economy, and the “Solidarity Pension Contribution” (<<Aporte Previsional Solidaria>>) for those whose pension payouts fall below a defined threshold, the “Maximum Pension with Solidarity Payment (<<Pensión Máxima con Aporte Solidaria>>). These are both financed directly from the government and are intended to aid the poorest sectors of society.

In addition to the mandatory AFP system and basic pensions/supplements mentioned above, employees may make voluntary contributions to funds.

The Social Agenda proposed by the current government—announced in response to the recent protests—contain several provisions addressing pensions:

Immediate 20% increase in the Basic Solidarity Pension

Immediate 20% increase in the Solidarity Pension Contribution

Subsequent increases in both cases for those older than 75

Government support for middle-class pension payments

Improvement for the support of elderly people with disabilities.

Monthly payouts are insufficient

The OECD states that pensions in Chile yield on average a replacement rate of 40%, defined as the individual net pension entitlement divided by net pre-retirement earnings, adjusted for taxes and other contributions. This is not great, falling well below the OECD average of 70%, but also doesn’t tell the whole story.

For instance, the United States’ average replacement rate is 49%, also below the OECD average, but pre-retirement earnings in the United States far exceed those in Chile. Furthermore, Americans also have access to a basic minimum pension in the form of Social Security. The average monthly benefit for Social Security is USD $1,461 / month, which is about 116% the federal minimum wage.

On the other hand, the average monthly payout for the entire AFP system in Chile was USD $315 / month in 2016, or 82% of the minimum wage. This also should be considered in light of the proportionally higher cost of living in Chile; making do with less than minimum wage is even harder here than in the US.

To put this in perspective: proportionally, an American whose only retirement income is from Social Security is better off than the average Chilean who receives a pension from an AFP.

The situation becomes bleaker for women. Stay-at-home parents, largely women, do not pay into a fund and are therefore tied to their spouses’ pension (if they are married). Women have replacement rates consistently lower than men (up to 107 percentage points; p. 87) yet live longer. Furthermore, the retirement age for women in Chile is five years less (60) than men. As AFP funds are spread over one’s expected lifetime, elderly women in particular suffer more as a result.

The AFP system is tremendously unpopular in Chile

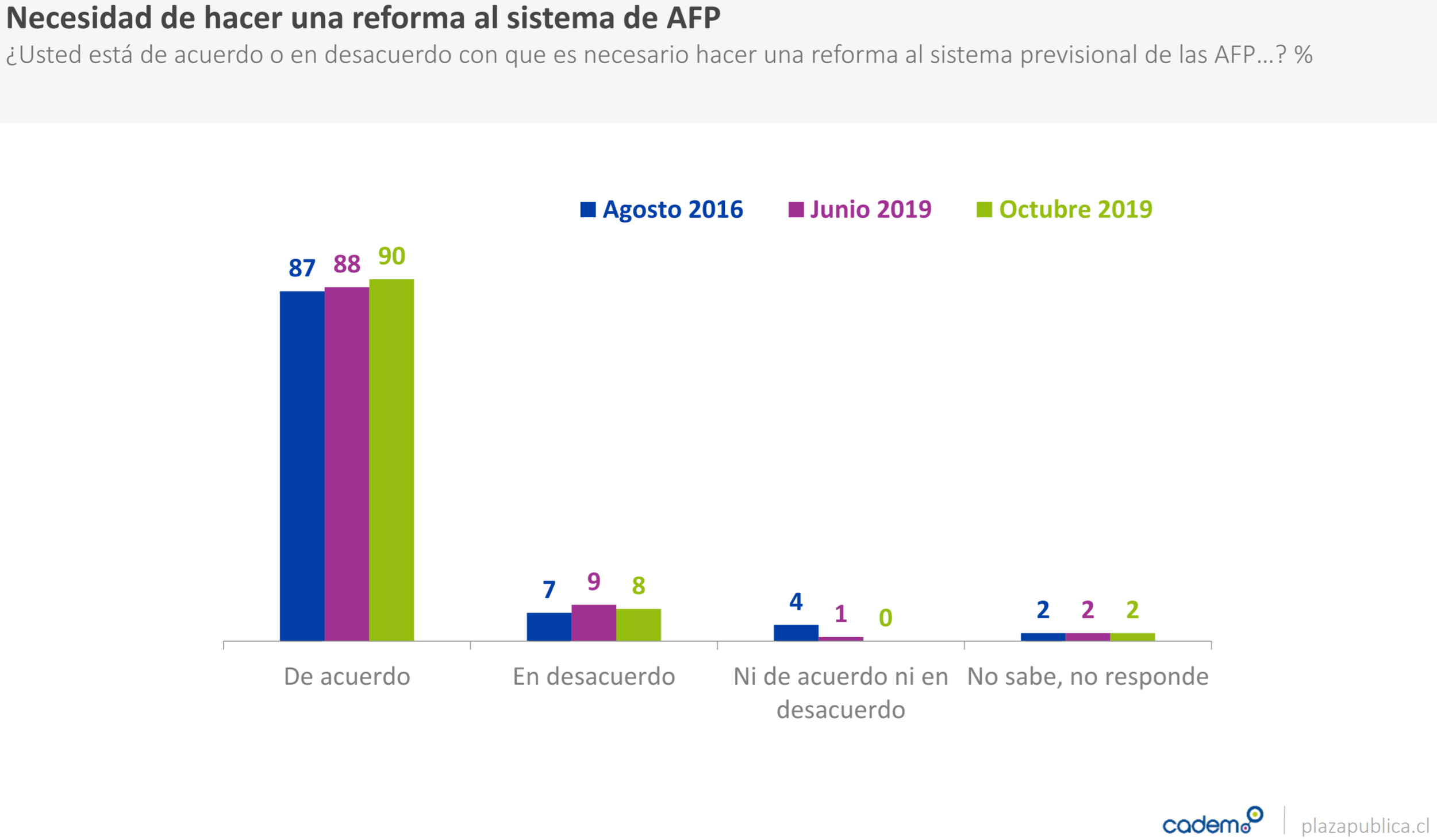

“Do you agree or disagree that it is necessary to reform the AFP pension system?”

Source: Cadem, 05 October 2019

There are countless reasons why an entire social movement against the AFP system has sprung up in Chile. Even if the AFP system functioned better, many would still chafe at the mandate to participate in a closed market. Distrust in the system is widespread given the opacity of AFP fee structures, which “makes it impossible to measure [the AFPs’] efficiency in managing the resources directly, because the commissions that members are charged cannot be compared directly with the yield obtained by the Pension Fund.” The concept of money managers is somewhat alien in Chile, and many consider outrageous the idea that another person can play financial games with your money—especially when your contribution is mandated by the state. This, as well as the lack of individual control over withdrawals of funds, leads many to believe that money contributed to an AFP no longer belongs to them, in either the figurative or the literal sense. Finally, in the leadup to the protests, the lack of faith in the current government’s ability or will to pursue meaningful reform in an honest manner was emphasized by controversies over a proposed 4% increase in pension contributions made by employers. Contrary to the government’s repeated insistence that the 4% would go directly to the savings of contributors, it was later revealed that the AFPs would still play a role in the administration of that fraction.

But what people really think about when it comes to AFPs is the state of the nation’s elderly. Retirees in Chile are suffering greatly due to inadequate pension payouts. In the 2016 edition of the Survey of the Quality of Life in Old Age (pdf), the number one fear of the elderly—beyond getting sick, and beyond death in the family—was “to have to depend on other people.” Earlier this year, an elderly couple were found dead in their homes, having died in a suicide pact as they were “tired of living” and no longer wished to rely on their families for support. The rate of suicide for adults over 60 has risen 163% since the return to democracy.

Speaking very broadly, the elderly in Chile are highly esteemed, and worry about the state of elders is at the emotional core of discontent at the AFP system. When people here visualize the effects of the AFP system, the image that comes to mind is the frequent sight of elderly people working manual jobs to supplement pensions that fall far below even the paltry average.

The AFP controversy encapsulates the existential struggle Chile now faces with its liberal economy

In spite of these grievances, ‘Chileans must pay more’ is a common solution offered by some commentators; others blame Chileans’ lack of financial literacy for low retirement returns. All the while, the Chilean pension system continues to receive plaudits from the world of financial experts.

Chile sits in a peculiar place in the world. At the top of Latin America but at the bottom of the OECD in all kinds of statistical indices, there’s an identity crisis as to which world Chile most pertains to. On the one hand, Chile strives for a quality of life comparable to that of the “First World.” Chileans are unremittingly told that the current economic system is responsible for our success, and to deviate from this course is to risk sliding back into the ugliness that supposedly characterizes the rest of South America.

On the other hand, the contrast between the perspective of the financial world and the experience lived on the ground generates a peculiar type of cognitive dissonance. In this headspace, one begins to wonder:

Why should I hand over any of my money to a pension fund, if I’ll never have enough to retire?

If public pensions were so bad, why are so many elders killing themselves under the current, superior system?

If economists in the “First World” really claim this system is one of the best in the world…maybe that is not the world to which I want to belong.

Even for those who are doing relatively well under the present system, there persists a silent imperative to fight: if not for your own fiscal wellbeing, than for that of the poor and the elderly.

You wouldn’t get 90% of the country clamoring for pension reform if it weren’t for a collective desire for a more just civil society for all.